ARISTON SCALDABAGNO ELETTRICO ORIZZONTALE PRO ECO EVO 80 H/5 5A.ARISTON COD. ARISTON 3201132-TuttoIdro

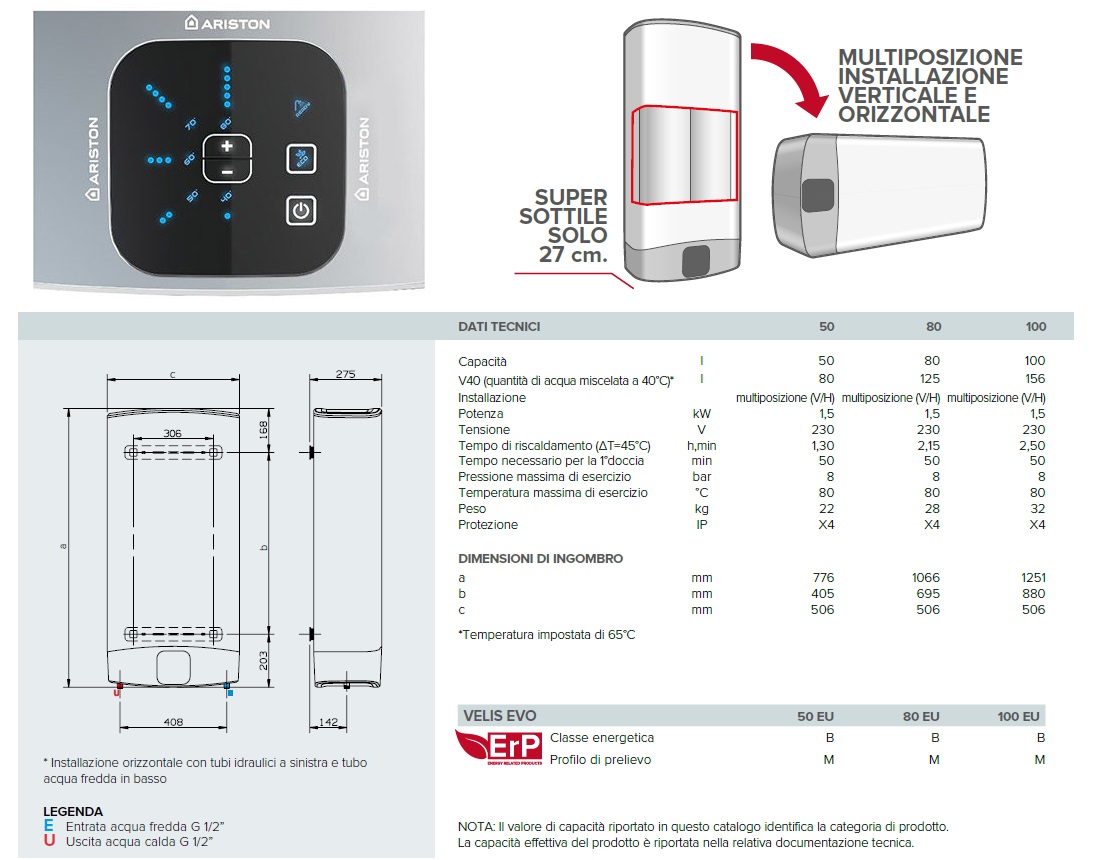

Ariston - Scaldabagno Elettrico ad accumulo 80 lt Slim Sottile Velis EVO EU Garanzia 5 anni | Ariston Velis Evo, Scaldabagni elettrici | Miele Arredo

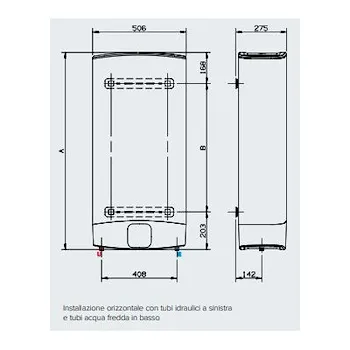

Scaldabagno elettrico per installazione orizzontale con capacità di 80 litri PRO1 R 80 V ES EU Ariston - Habitium®